- Anesthesiologist specializing in non-surgical spine care

Fellowship-trained in Interventional Spine

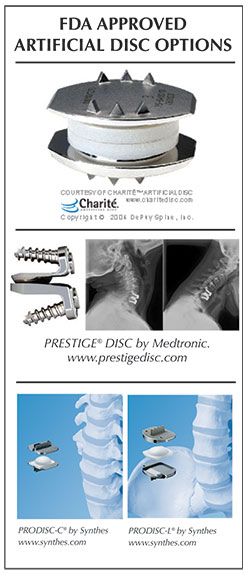

Artificial Disc

History | Problems with the artificial disc | Lumbar vs. Cervical Artificial Disc | How artificial discs work | Benefits | The Lifespan of an artificial disc

History of the artificial disc for spine

Perhaps the most anticipated advance in spine surgery over the past 20 years was the arrival of the artificial disc. The first artificial disc in the United States received formal approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for widespread use in the United States on October 26, 2004. While this technology was somewhat new to the U.S., artificial discs were used in Europe for a decade or so before that.

There are several models of artificial discs approved by the FDA for use in the United States including Charite, Prestige, ProDisc and Mobi-C, and that number is expected to grow as new models emerge on the scene and surgeons become trained in their use. Each disc is designed for use either in the low back (lumbar area) or neck (cervical area). Mobi-C and Prestige are approved by the FDA for up to two levels in the cervical spine (neck).

In addition, other artificial disc models are available on a limited basis through “clinical trials” where a patient agrees to be part of clinical study designed to measure the success of a new disc model, which will be part of an FDA study. Patients who participate in a clinical trial can gain access to the most current technology, even though it has yet to gain FDA approval for use in the United States.

In addition, other artificial disc models are available on a limited basis through “clinical trials” where a patient agrees to be part of clinical study designed to measure the success of a new disc model, which will be part of an FDA study. Patients who participate in a clinical trial can gain access to the most current technology, even though it has yet to gain FDA approval for use in the United States.

In principle, the artificial disc is a great concept in that it restores motion between the vertebral bodies, where a fusion locks them into place. However, it’s hard to improve or even match what Mother Nature has given us.

Problems with the artificial disc

It is important to remember that this artificial disc technology is still evolving with new implants continually in development. Your spine surgeon is the best resource to discuss if it is appropriate for you, and what model of artificial disc is best suited for your case.

Many spine surgeons currently are cautious about artificial discs because of their limitations, concerns about complex revision surgery to remove a worn out artificial disc, and the prospect of yet newer versions coming out which make older ones obsolete.

For example, when the artificial disc first received FDA approval, too many surgeons were quick to implant this new technology, and as a result many patients had problems.

Some artificial disc implants wore out too soon which required complex revision surgery and produced less than ideal outcomes.

Another concern about the existing discs is that while side-to-side motion is preserved, there typically is no up and down shock absorption provided with the man-made implants. This can accelerate wear on the artificial disc joint when the person is active.

Lumbar artificial discs vs. cervical artificial discs

There is a big difference in the artificial discs used in the lumbar (low back) area, and the artificial discs used in the cervical (neck) area. Because of the weight of the body and the rotational stress that the trunk places on discs in the low back (lumbar) area, more stress is placed on artificial discs in the lumbar area than in the neck (cervical) area, which only supports the weight of the head.

A second issue relates to the ease of the artificial disc surgery and any necessary revision surgery to replace a worn out artificial disc. Because the surgeon must access the front of the spine, an incision is made in the abdomen for lumbar discs and in the front of the neck for cervical discs.

Generally speaking, many spine surgeons believe access to the cervical discs can be easier than the lumbar discs.

How artificial discs work

The artificial disc concept is intended to be an alternative for spinal fusion surgery. Each year in the U.S., more than 200,000 spinal fusion surgeries are performed to relieve excruciating pain caused by damaged discs in the low back and neck areas.

During a fusion procedure, the damaged disc is typically replaced with bone from a patient’s hip or from a bone bank. Fusion surgery causes two vertebrae to become locked in place, putting additional stress on discs above and below the fusion site, which restricts movement and can lead to further disc herniation with the discs above and below the degenerated disc. An artificial disc replacement is intended to duplicate the function level of a normal, healthy disc and retain motion in the spine.

When a natural disc herniates or becomes badly degenerated, it loses its shock-absorbing ability, which can narrow the space between vertebrae. In fusion surgery, the damaged disc isn’t repaired but rather is removed and replaced with bone that restores the space between the vertebrae. However, this bone locks the vertebrae into place, which can then damage other discs above and below.

A common aspect of all artificial discs is that they are designed to retain the natural movement in the spine by duplicating the rotational function of the discs Mother Nature gave us at birth. Most artificial disc designs have plates that attach to the vertebrae and a rotational component that fits between these fixation plates. These components are typically designed to withstand stress and rotational forces over long periods of time. Still, like any manmade material, they can be affected by wear and tear.

The benefits of artificial discs

Some of the main benefits of the artificial disc parallel that of knee replacement and hip replacement. This can include the following benefits:

- An artificial disc in the neck or back, in principle, is designed to retain motion in that particular segment of the spine.

- It prevents degeneration of disc levels above and below the affected disc

- There is no bone graft required

- There can be a quicker recovery and return to work or activity

- It can be a less invasive and less painful surgery than a fusion

- There can be less blood loss during surgery

The lifespan of an artificial disc

When treating knee and hip replacement patients, orthopedic surgeons try to postpone the implantation of an artificial joint until a patient is at least 50 years old so that they do not outlive their artificial joint, which typically lasts anywhere from 15 to 20 years. Revision surgery, which may be necessary to replace a worn-out artificial joint, can be complex.

This is also a concern with the artificial disc. Unlike knee and hip replacement patients who are typically in their 50s or 60s, many patients can benefit from artificial disc technology at a much younger age — in their 20s or 30s. Therefore, the implantation of an artificial disc in younger patients can raise a surgeon’s concern about the potential life span of the artificial disc in the spine and the need for revision surgery to replace a worn-out artificial disc, which can be complex.

In summary, some spine surgeons may be cautious about the use of artificial discs for the following reasons:

- Wear and tear on artificial joints cant require revision surgery in 10 to 20 years that can be extremely complex.

- Most artificial disc implants only address rotational forces, not the up and down shock absorbing function of the natural disc.

- Overweight people can wear out a lumbar disc prematurely.

- New artificial discs are continually in development, however FDA approval is a lengthy process.

- There are not many 20-year-long studies that show the long-term effects of wear and tear on artificial disc implants.

Non-surgical Spine Care

-

Andrew “Gunter” Cain, MD

Andrew “Gunter” Cain, MD

Affiliated Spine Surgeons

can be reached at 501-224-0200

-

Tim Burson, MD

Tim Burson, MD- Board-Certified

Neurological Surgeon

- Board-Certified

-

-

-

Blake Phillips, MD

Blake Phillips, MD- Board-Certified

Neurological Surgeon

- Board-Certified

-

Jonathan Reding, MD

Jonathan Reding, MD- Board-Certified

Neurological Surgeon

Fellowship-Trained Neurosurgeon

- Board-Certified

Back to Life Journal

Home Remedy Book